Impressionism. A movement in art, generally in painting, that originated in France in the 1860s and had an enormous impact on Western art over the following half-century. As an organized movement, Impressionism was purely a French phenomenon, but many of its ideas and practices were adopted in other countries, and by the turn of the century it was a dominant influence on avant-garde art in Europe (and also in the USA and Australia). In essence, its effect was to undermine the authority of large, formal, highly finished paintings in favour of works that more immediately expressed the artist's personality and response to the world.

The Impressionists were not a formal group with clearly defined principles and aims; rather they were a loose association of artists linked by some community of outlook who banded together for the purpose of exhibiting, most of them having had difficulty in getting their work accepted for the official Salon (they held eight group shows, all in Paris, in 1874, 1876, 1877, 1879, 1880, 1881, 1882, and 1886). The main figures involved were (in alphabetical order) Cézanne, Degas, Manet, Monet, Camille Pissarro, Renoir, and Sisley; Berthe Morisot, too, played a central role in the movement. Frédéric Bazille was part of the original nucleus but died tragically early in 1870; the minor figures included Armand Guillaumin, who was the last survivor of those who showed in the 1874 exhibition, dying in 1927. Monet, Renoir, and Sisley met as students, and the others came into contact with them through the artistic café society of Paris. There were friendly ties of varied degrees of intimacy linking each of them to most of the others, but Degas and even more Manet were set somewhat apart because they came from a higher stratum of society than the others, and the artists' commitment to Impressionism varied considerably (Manet was much respected as a senior figure, but he never exhibited with the group). They were united, however, in rebelling against academic conventions to try to depict their surroundings with spontaneity and freshness, capturing an ‘impression’ of what the eye sees at a particular moment, rather than a detailed record of appearances. Their archetypal subject was landscape (and painting out of doors, directly from nature, was one of the key characteristics of the movement), but they treated many other subjects, notably ones involving everyday city life. Degas, for example, made subjects such as horse races, dancers, and laundresses his own, and Renoir is famous for his pictures of pretty women and children.

In trying to capture the effects of light on varied surfaces, particularly in open-air settings, the Impressionists transformed painting, using bright colours and sketchy brushwork that seemed bewildering or shocking to traditionalists. The name ‘Impressionism’, in fact, was coined derisively, when the painter and critic Louis Leroy (1812–85) latched onto a picture by Monet, Impression: Sunrise (1872, Mus. Marmottan, Paris), at the group's first exhibition, heading his abusive review ‘Exposition des Impressionistes’ (Le Charivari, 25 Apr. 1874); he dismissed the group as a whole as ‘hostile to good manners, to devotion to form, and to respect for the masters’. Although the critical response to the Impressionists was not as one-sided as is sometimes suggested, Leroy's attitude prevailed in conservative circles for many years; for example, when Gustave Caillebotte left his superb Impressionist collection to the French nation in 1894, Jean-Léon Gérôme wrote that ‘For the Government to accept such filth, there would have to be a great moral slackening.’ However, by the the time of the final exhibition in 1886 the Impressionists as a whole were starting to achieve critical praise and financial success (helped by the dedicated promotion of Durand-Ruel), and during the 1890s their influence began to be widely felt (by this time the group had broken up and only Monet continued to pursue Impressionist ideals rigorously).

Few artists outside France adopted Impressionism wholesale, but many lightened their palettes and loosened their brushwork as they synthesized its ideas with their local traditions. It was perhaps in the USA that it was most eagerly adopted, both by painters such as Childe Hassam and the other members of The Ten and by collectors ( Mary Cassatt helped to develop the taste among her wealthy picture-buying friends). It also made a significant impact in Australia, with Tom Roberts playing the leading role in its introduction. In Britain, Sickert and Steer are generally regarded as the main channels through which Impressionism influenced the country's art, but the differences between their work shows how broadly and imprecisely the term has been used (at the time, D. S. MacColl commented that it was applied to ‘any new painting that surprised or annoyed the critics or public’). For a few years around 1890, Steer painted in a sparklingly fresh Impressionist manner, but his style later became more sober; Sickert adopted the broken brushwork of Impressionism (as did his followers in the Camden Town Group), but he used much more subdued colour, and he had a taste for quirky, distinctively English subject matter. In contrast, the painters of the Newlyn School often painted out of doors in conscious imitation of the French and used comparatively high-keyed colour, but they generally did not adopt Impressionist brushwork. Accordingly, many authorities think that among British artists, only Steer—and he only briefly—can be considered a ‘pure’ Impressionist.

In addition to prompting imitation and adaptation, Impressionism also inspired various counter-reactions—indeed its influence was so great that much of the history of late 19th-century and early 20th-century painting is the story of its aftermath. The Neo-Impressionists, for example, tried to give the optical principles of Impressionism a scientific basis, and the Post-Impressionists began a long series of movements that attempted to free colour and line from purely representational functions. Similarly, the Symbolists wanted to restore the emotional values that they thought the Impressionists had sacrificed through concentrating so strongly on the fleeting and the casual.

IAN CHILVERS.

"Impressionism."

The Oxford Dictionary of Art.

2004. Retrieved

June 05, 2012

from Encyclopedia.com:

http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1O2-Impressionism.html

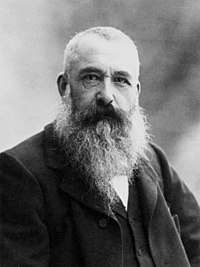

| Claude Monet | |

|---|---|

Claude Monet, photo by Nadar, 1899. |

|

| Birth name | Oscar-Claude Monet |

| Born | 14 November 1840 Paris, France |

| Died | 5 December 1926 (aged 86) Giverny , France |

| Nationality | French |

| Field | Painter |

| Movement | Impressionism |

| Works | Impression, Sunrise Rouen Cathedral series London Parliament series Water Lilies Haystacks Poplars |

| Patrons | Gustave Caillebotte, Ernest Hoschedé, Georges Clemenceau |

| Influenced by | Eugène Boudin, Johan Jongkind, Gustave Courbet |

Claude Monet: (14 November 1840 – 5 December 1926) was a founder of French impressionist

painting, and the most consistent and prolific practitioner of the

movement's philosophy of expressing one's perceptions before nature,

especially as applied to plein-air landscape painting. The term Impressionism is derived from the title of his painting Impression, Sunrise (Impression, soleil levant).

Hiç yorum yok:

Yorum Gönder